Q&A with Judge Charles Burns

In honor of Fair Chance Month, we asked Judge Charles Burns about the (W)RAP program, a transformative justice alternative for individuals with convictions related to non-violent, drug-related substance abuse. Cara Collective has engaged more than 130 people referred by Judge Burns through (W)RAP, and our deepening partnership will continue to serve justice-involved individuals who are ready to overcome addiction and rebuild their lives.

- Tell us about the (W)RAP program and what separates it from the traditional court experience.

(W)RAP is an acronym for Rehabilitation Alternative Probation and Woman’s Rehabilitative Alternative Probation. The (W)RAP program was started in 1998 as a collaborative approach to criminal justice serving high-risk and high-needs individuals who have felonies connected to drug-related substance abuse. These individuals are high risk, but that doesn’t mean they are a high risk to the community. They have committed non-violent crimes and are at risk of recidivism, and they need intensive services to quit using drugs.

Many of the individuals who go through our program have been in the criminal justice system for decades, but going to the penitentiary doesn’t solve the problem. Addiction isn’t a moral failure. Substance abuse disorder is a disease. This program addresses the core issues underneath addiction often linked to extended trauma. We focus on intensive treatment that breaks the cycle of recidivism and addiction through transformative justice.

- What supports and services does (W)RAP provide that make it a successful alternative to incarceration?

Once individuals join our program, we assess their needs and get them treatment right away. We often have people stay in a halfway house or recovery home and get intensive outpatient care for about three months. During that time, they attend individual and group classes with our treatment partners. They meet with their probation officer regularly and get drug tested periodically. We get them involved in self-help groups and recovery support groups.

Then, when they finish treatment, we have to address housing: they either go back to where they are living, or we find structured housing for longer-term living. We evaluate on a case-by-case basis. Once they are situated in their living situations, we bring in Cara to help them secure gainful employment. This is important because some of our individuals have never had a job. They couldn’t maintain a job because of their addiction.

This approach is a much better alternative than incarceration because it focuses on addiction being a disease. You wouldn’t ignore your diabetes or any other health concern – that would have serious consequences. We want people to succeed and address what causes the sickness. You can’t incarcerate someone and expect them not to have the same habits when they leave. Also, in terms of dollars, it costs quadruple the amount of money to incarcerate someone than to have them go through this program. It’s cost effective to taxpayers and is a huge benefit not just for the individual but to society.

- What does it mean for someone to graduate from (W)RAP?

The program takes about two years to complete. The length of time is probation based, so you can get through it as fast as a year or it may take more than two in some cases. One aspect that makes our program unique is we don’t dismiss people from the program if they stumble. If someone relapses but they are willing to keep doing the work, I’ll work with them.

Individuals are evaluated based on milestones. They must go through treatment and stay clean. They have to be self-sufficient, and in most cases that means having a job that you can maintain to afford life’s necessities. The milestones are divided into four specific phases, and once we determine all four are complete, an individual is ready to graduate.

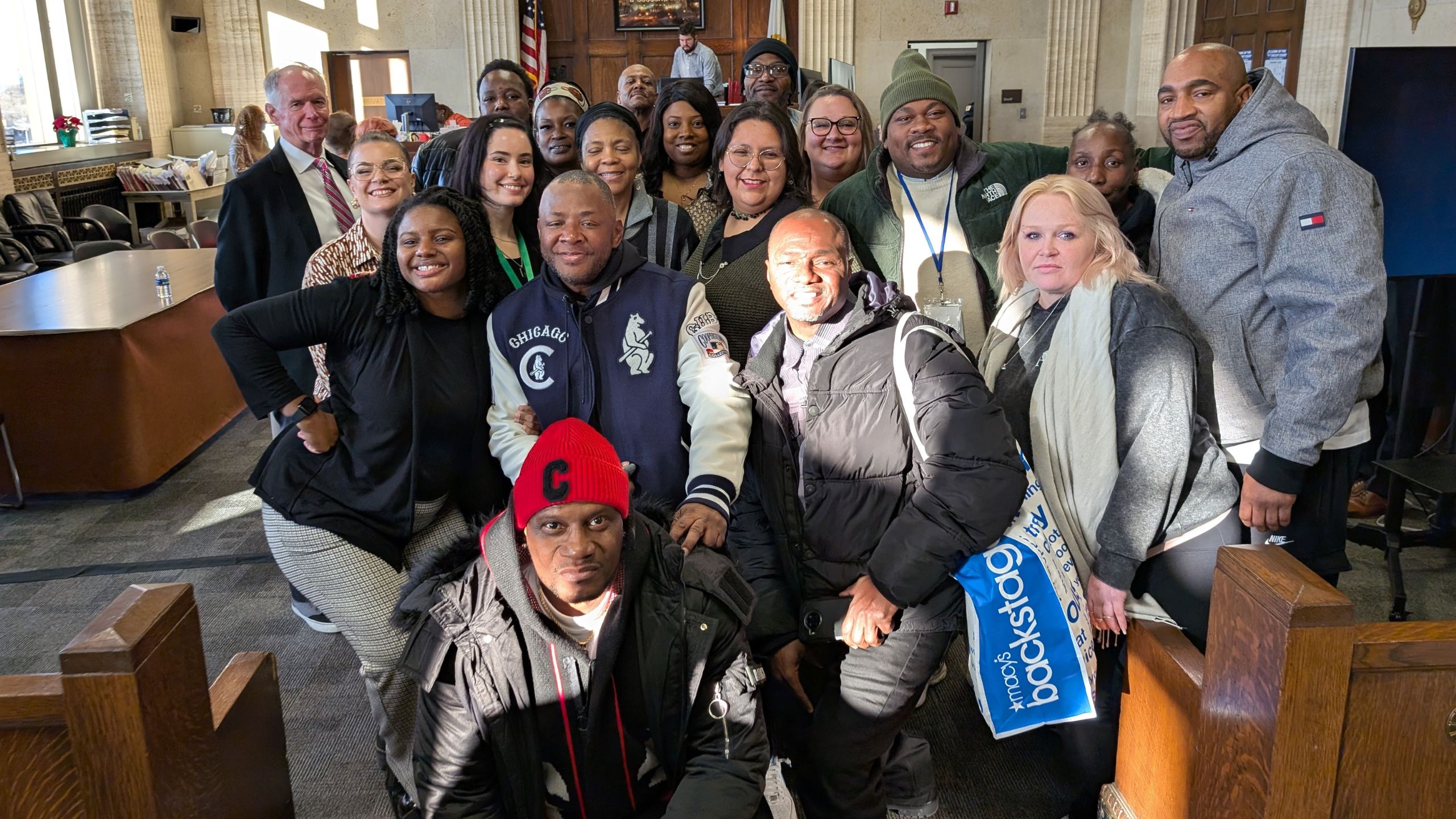

We hold a graduation ceremony every year in my courtroom, where all the graduates have the option to share a little bit about their journeys. It’s an inspiring day and there are always tears. Family members of the graduates say things like “Thank you for giving me my son back.” Graduates often say, “I would be dead if it wasn’t for this program.”

On Graduation Day, I dismiss the charge that brought the individual into the (W)RAP program. Then, after 61 days post-graduation, I partner with Cabrini Green Legal Aide to personally expunge their records of any non-violent, drug-related convictions from the past five years.

- How has your partnership with Cara helped (W)RAP participants succeed?

We have been partnering with Cara for at least ten years, and I really can’t thank Cara enough. Cara works so well for participants in our program because of the wraparound support you provide. Everything from helping someone get resources for fixing their credit to providing clothing for interviews. A lot of workforce programs might help people build a resume and send them out, but Cara provides wraparound support similar to the (W)RAP program – we kind of mirror each other and have great communication between our teams.

The other thing I love about Cara is the job opportunities you provide. They are good jobs where people can stay and grow. Even people who were reluctant to come to Cara go through the program praising it. Cara is working to open doors for people with backgrounds, and justice-involved job seekers can be hard to place into jobs.

- What is your hope for the future of the program?

I hope to see the (W)RAP program sustain and grow. We need programs like (W)RAP because when the justice system decriminalizes addiction-related cases, they are not helping anyone because people can’t quit on their own. We need these programs because I can’t help someone if I can’t get them into the program.

A good example was years ago, a woman named Etta was in the program, and she had lived a hard life in Appalachia. She had a terrible struggle with addiction. She was in a couple different programs, and I knew it wasn’t going to work out, but I let her run those out. She kept relapsing, and so I said, “No, we are going to do this my way.” We got her into treatment and found her housing. She started succeeding, and she would come into the court beaming and so proud. Everyone loved her.

One Monday I came into work and learned Etta had died. I knew she hadn’t relapsed. She had been sick for a month or two before she died of natural causes. My takeaway was that if we had gotten her five or six years earlier, she would have had less continued abuse on her body. Her body had refused to fight when she died.

That’s why we have to get more justice-involved individuals who struggle with addiction into this program. We have to sustain and grow.

- What do you wish everyone knew about justice-involved individuals?

Justice-involved job seekers are qualified and motivated. They work hard and love their jobs. It’s unfair to judge someone from when they were sick with addiction; they weren’t performing at their best. We need to treat addiction as a sickness and not as an imperfection of a person.

Justice-involved individuals believe they can’t get a job after going to the penitentiary, but that’s not true. Employers need workers. Who would have thought that someone with felony convictions could work at some of the city’s best hospitals or in programs like the CTA Second Chance Program? We need employers to provide as many jobs as they can, and then they will see justice-involved employees show up eager and ready to get after it.

We are grateful to Judge Burns for sharing about (W)RAP and for his ongoing commitment to helping justice-involved individuals succeed. Would your employer be interested in creating opportunities for justice-involved individuals? Read our case studies on how leading employers adopted fair chance hiring.